- Home

- Scott Farris

Kennedy and Reagan Page 20

Kennedy and Reagan Read online

Page 20

Kennedy and Reagan are each entitled to substantial credit. They were widely read and skilled writers, and in a democracy such faculty with words is important to political success.

Kennedy had seriously considered a career in journalism, and he had done credible work in his short time as a correspondent with the Hearst newspapers. Whatever help he received from Sorensen on Profiles in Courage or from Arthur Krock on Why England Slept, he had initiated both projects, conceptualized each project, done significant amounts of research and writing, and edited and approved those parts he did not personally write.

Before hiring Sorensen in 1953, Kennedy had also demonstrated he was more than capable of writing his own speeches. His congressional secretary, Mary Davis, marveled at Kennedy’s ability to dictate his speeches so fluently. “He just had it stored in the back of his mind somewhere, and when he needed the facts, when he needed that information, he could bring it right out and it was there in final form as I was taking it down in shorthand,” she said. “ . . . When he wanted to write a speech he did it, most of it. I would say 99 percent of that was done by JFK himself.”

Thurston Clarke, who has devoted an entire book to Kennedy’s famed inaugural address, ultimately concludes that Kennedy, not Sorensen, was the primary author of what is generally considered the third-best inaugural address in American history, behind FDR’s first inaugural and Lincoln’s second.

Kennedy’s ability as a writer is underappreciated, in part, because, as Davis noted, he preferred dictating his thoughts rather than writing them out in his own hand. He had gotten into this habit during college as the rare undergraduate who could afford to hire stenographers and typists, but he was also likely aware that Churchill wrote primarily by dictation. Audiotapes of Kennedy’s dictation while still a congressman and senator “show him seldom pausing or repeating himself,” Clarke said. “His sentences are short and simple, shorn at their birth of qualifiers and adjectives, and one sometimes hears ideas and phrases destined for his inaugural address.”

The breadth of Kennedy’s communication skills were on display at the 1956 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, in which he gave three key addresses, each seen by a national television audience. On opening night, Kennedy narrated a film on the history of the Democratic Party produced by former MGM president Dore Schary. Voicing over the highly sentimental piece in his crisp and cultivated New England accent, “Kennedy came before the convention tonight as a movie star,” reported the New York Times. Because Kennedy had created such a sensation, Stevenson then asked Kennedy to offer one of the nominating speeches for his candidacy. Kennedy was happy to do so, as he hoped Stevenson would select him as his vice-presidential running mate.

But Stevenson was ambivalent about Kennedy. He thought he was too young and inexperienced. He also intensely disliked Kennedy’s father, and he thought Kennedy’s Catholicism would hinder the campaign. In addition, influential liberals, such as his close friend Mrs. Roosevelt, opposed Kennedy because of his failure to censure McCarthy. On the other hand, other leading vice-presidential contenders had their own baggage. Convinced he could not make a selection acceptable to all elements within the Democratic Party, Stevenson invited the convention delegates to choose their vice-presidential nominee themselves.

The next twenty-four hours were pandemonium as Kennedy and a half-dozen other men scrambled to put together last-minute campaigns for delegates. The race came down to Kennedy and maverick Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver. Kennedy came within forty votes of securing the nomination on the second ballot, with most of his strength coming from Southern delegates, not Northeastern liberals, because of Kefauver’s apostasy on civil rights and lingering liberal resentment over Kennedy’s McCarthy problem. But then the Tennessee delegation decided to support its native son after all, and Kefauver swept past Kennedy to secure the nomination by a vote of 775½ to 589.

Within minutes, Kennedy was at the Chicago Amphitheater making his way to the rostrum. In a brief extemporaneous speech of less than two minutes, Kennedy thanked the delegates for their support and praised Kefauver’s nomination, urging that it be made unanimous. While Kennedy was despondent, it made for good television, as he spoke in “subdued, controlled tones that contained the passion of a magnanimous loser.” Kennedy’s appeal was such that even when Kefauver took the podium to accept the nomination, the network cameras kept cutting back to Kennedy, gauging his reaction.

Even though he was not on the ballot, Kennedy was the big Democratic winner in 1956. Stevenson lost to Eisenhower by an even bigger margin than he had in 1952, but in the year after the election, Kennedy received more than 2,500 speaking invitations and accepted 144 of them, which took him to forty-seven different states. By 1958 he was receiving a hundred speaking requests a week.

Eight years later, Reagan was also considered the big Republican winner in Barry Goldwater’s unsuccessful 1964 presidential campaign because he, too, gave a remarkably well-received nationally televised speech—the speech that he had been giving on behalf of GE and which he continued to give even after General Electric Theater was taken off the air and Reagan went on to host Death Valley Days instead.

Reagan had been giving speeches at an even greater rate than Kennedy during the 1950s, and before even more people. In his first year with GE, Reagan estimated he had already met one hundred thousand GE employees at 185 facilities across the country. But he addressed more than GE employees. Because part of his role was acting as an evangelist for electricity, a typical visit to a GE plant might also include a speech to a local civic club, a press conference, and a presentation to a local high school or college. Plus, Reagan was also already moving into politics. He addressed a rally of Dr. Fred Schwarz’s Christian Anti-Communist Crusade in 1961, and he spoke on behalf of California congressman John Rousselot, a leading member of the John Birch Society.

Reagan also gave more than two hundred speeches during the 1960 presidential campaign on behalf of Nixon, the politician he had previously denounced for being dishonest and in thrall to special interests. Now, in a sign of how clearly Reagan had moved to the right politically in just a decade, Reagan wrote Nixon that he found Kennedy’s proposed New Frontier program “a frightening call to arms” for bigger government, adding of Kennedy, “under the tousled boyish haircut is still old Karl Marx.” There is no record of a response by Nixon to Reagan’s letter, though he attached a note for his staff that read, “Use him as speaker whenever possible. He used to be a liberal!”

By his own estimation, Reagan said he spent more than 250,000 minutes giving speeches during his eight years at GE. Given that “The Speech,” as it would become known after its performance during the Goldwater campaign, ran roughly thirty minutes, this meant Reagan would have given his talk more than eight thousand times. Since GE did not tell Reagan what to say (except once when they told him to stop attacking the Tennessee Valley Authority, a major GE customer), The Speech was the work of Reagan and no one else.*

* Reagan would later imply that GE fired him in 1962 because he had become too politically active, while scholar Garry Wills believes GE was worried about the government’s investigation of MCA and Reagan’s role in granting MCA the waiver to become a television producer. GE executives said Reagan was dropped and General Electric Theater canceled because Bonanza was killing it in the ratings. Whatever the reason, MCA got Reagan a new job hosting Death Valley Days for Borax—The Twenty Mule Team!

Like Kennedy, Reagan had considered himself a writer from a young age. Reagan biographer Edmund Morris, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Theodore Roosevelt, reviewed a series of short stories and essays that Reagan wrote in college and concluded that his prose shared the “lyrical sensibilities” of those produced by a young Theodore Roosevelt, usually considered one of the three or four best writers among all our presidents. Morris cited a scene in one of Reagan’s stories in which a young canoeist finds himself in rough weather—“The

stern drops from under you—then up it comes on the crest and you surge forward borne on the very wave that has just defeated you”—to conclude that he was already demonstrating an ability to write with a “physical forcefulness” that would serve him well in political speechmaking.

Having been a sportswriter and frustrated screenwriter, Reagan wrote most of his own speeches until he became president, but even then, at least during his first term, he remained actively engaged in the editing of his speeches.*

* Peggy Noonan, a speechwriter for President Reagan from 1984 to 1986, recalled that by that period in the administration, Reagan’s speeches were generally the work of committees, a process she compared to taking a bunch of beautiful, perfect, crisp vegetables and grinding them into a “smooth, dull, textureless puree.” Excepting the addresses he gave on the fortieth anniversary of D-Day and to commemorate the space shuttle Challenger disaster, even Reagan seemed dispirited by the dullness of most of his later addresses, once wistfully reminding Noonan, “I used to write my own speeches, you know.”

Between the end of his time as governor of California and his 1980 campaign for president, Reagan also wrote daily nationally syndicated radio commentaries. Scripts for nearly seven hundred of these five-minute-long commentaries in Reagan’s own hand have survived, indicating that Reagan took his writing and the articulation of his political thoughts very seriously.

Reagan’s wife, Nancy, along with many former Reagan aides, said that despite critics who charged Reagan with being lazy and incurious, he was, in fact, a “voracious reader” his entire life, constantly absorbing new facts and information and, contrary to myth, seldom spent his nights watching television. Rather, Mrs. Reagan said, “When I picture those days, it’s him sitting behind that desk in the bedroom, working.” An aide who traveled with Reagan added that Reagan “would constantly be writing.” As with Kennedy’s dictation, these manuscripts in Reagan’s longhand indicate his first drafts usually came out fully formed and in need of little revision.

Unlike Kennedy, Reagan had no aspiration to be considered an intellectual. As a GE public relations officer recalled, The Speech that Reagan developed was about “old American values—the ones I believe in, but it was like the Boy Scout code, you know, not very informative. But always lively, with entertaining stories.”

If Reagan’s prose was neither elegant nor intellectually high-minded, it nevertheless moved people. When the Goldwater campaign found itself strapped for cash, Reagan was asked if he would deliver The Speech on national television as a commercial, which the Goldwater campaign would call “A Time for Choosing.”

Goldwater and his aides had initially balked at putting Reagan on television, both because they thought The Speech was no more than a collection of antigovernment clichés and because they thought that it would reinforce Goldwater’s image as an extremist. But it was such a success that “viewers overnight contributed $1 million to the foundering Goldwater campaign,” and Reagan’s performance was called the “most successful political debut since William Jennings Bryan electrified the 1896 Democratic Convention with his ‘Cross of Gold’ speech.”

In his concluding paragraph, Reagan, knowing good material when he saw it, cribbed passages from FDR, Lincoln, and Churchill, saying, “You and I have a rendezvous with destiny. We can preserve for our children this the last best hope of man on earth, or we can sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness. If we fail, at least let our children and our children’s children, say of us we justified our brief moment here. We did all that could be done.” On the printed page, the words appear as Goldwater first saw them, pessimistic, even apocalyptic, but as Reagan gave them in his sunny baritone voice, confidently smiling and without any hint of menace, those who heard it in their living rooms did not hear despair, but instead “felt they were being summoned to a vital battle that would surely end in victory.”

CHAPTER 12

THE MAD DASH FOR PRESIDENT

John F. Kennedy’s rapid rise to the presidency, without the backing of his party’s hierarchy or any particularly distinguished public policy accomplishments to justify it, changed the way we choose our presidents. After Kennedy, as one biographer said, “the only qualification for the most powerful job in the world was wanting it.”

Ronald Reagan, who also possessed, in the words of William F. Buckley Jr., “precipitate ambitiousness,” was inspired by Kennedy’s meteoric rise. Immediately after his extraordinarily successful appearance on national television on behalf of the Goldwater campaign, Reagan, while still hosting Death Valley Days on television, and his leading conservative backers began plotting his path to the presidency—even though he was fifty-five years old and had never held or even sought previous elective office. As early Reagan supporter, businessman, and conservative activist Henry Salvatori said, “Look at John F. Kennedy. He didn’t have much of a record as a senator. But he made a great appearance.”

Appearance—that was what Nixon blamed for his loss to Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election. It was regrettable for those who, like himself, valued substance, Nixon said, but television was now such a force in politics, indeed the primary source of news for most voters, that “one bad camera angle on television can have far more effect on the election outcome than a major mistake in writing a speech.”

Nixon also noted that Kennedy held an advantage by having been actively running for president since he lost the vice-presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention in 1956. Actually, Nixon was off by a decade; Kennedy had been running for president since 1946. When Kennedy decided to run for Congress in 1946, it was understood that it was the first step toward his father’s goal of making a Kennedy son chief of state.

Reagan, too, essentially ran for president for fourteen years before being elected on his third try in 1980. By then he was sixty-nine years old and had served two terms as governor of California. But well before election day 1980, in fact just ten days after Reagan had been voted in as governor of California in 1966 and six weeks before he had even taken his oath of office in Sacramento, he and his supporters held their first strategy session to plan his 1968 presidential campaign.

During his campaign for governor, while being coached (and bored) with local politics and statistics on mental health hospitals and pesticide runoff, Reagan turned to an aide and said, “Damn, wouldn’t this be fun if we were running for the presidency?” Part of Kennedy and Reagan’s success was that they truly did think politics was fun. Though his parents had not thought of him as a natural politician, Kennedy, like Reagan, enjoyed the competition that politics provided—perhaps, also like Reagan, as a substitute for the football glory that had eluded him as a schoolboy.

But each man also demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for hard work and an ability to focus on the goals they had set for themselves. From the times Kennedy and Reagan had committed to political careers, their sole quests were the presidency. Being a congressman, senator, or governor provided no great satisfaction beyond how far such offices advanced each politician toward the White House. They were just rungs on a ladder.

Buoyed by the remarkable run of successes Kennedy and Reagan had each enjoyed since they were young men, they had no reason to believe that the greatest political office in the world was beyond their grasp. Further, nothing they had achieved before had been done in a conventional way. Kennedy had become a best-selling author from writing a senior thesis and had become a war hero by losing his boat. Reagan became a movie star by being a sports announcer who never actually saw a game and a wealthy corporate spokesman because he had been the president of a labor union.

In seeking the presidency, they defied political convention as well. Neither waited their turn, nor worried about receiving the blessing of their respective parties’ establishment. After Kennedy and Reagan, national party conventions dominated by party bosses and power brokers would only ratify the presidential no

minees, not select them. That work would have already been done by the party rank and file during the primaries and caucuses. Kennedy and Reagan, running as outsiders and underdogs—personas they would take into their presidencies with mixed results—were the people’s choice, which likely explains a great deal about their enduring popularity.

Presidential primaries had existed for decades (Oregon established the first in 1910), but they had mattered little in the candidate selection process—until Kennedy came along. Kennedy made presidential primaries matter primarily just by saying they did. Since Al Smith’s disastrous defeat in 1928, there remained the lingering question of whether a Roman Catholic could be elected president. Kennedy used the primaries he won—and he won all he entered—particularly the one in largely Protestant West Virginia, to prove to the national media and party activists that his religion would not be an impediment to his becoming president.

Since 1960, excepting the strange year of 1968, when assassination ended Robert Kennedy’s candidacy and Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic nomination without entering a single primary, results from presidential primaries and caucuses have been the method by which the Republican and Democratic Parties have chosen their nominees. Of course, competing in primaries requires far more money than just renting a hospitality suite at a national convention, so the new method of securing a presidential nomination now also requires huge financial resources, whether one’s own, as in Kennedy’s case, or secured from others through campaign contributions. That financial burden, too, is a Kennedy legacy.

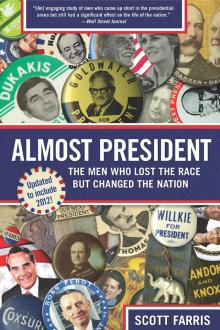

Almost President

Almost President Kennedy and Reagan

Kennedy and Reagan