- Home

- Scott Farris

Almost President Page 2

Almost President Read online

Page 2

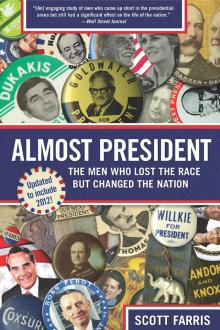

Chapters two through ten feature nine men whose candidacies have had the greatest impact on our political system, and where that impact can still be felt today. Those nine are Henry Clay, who resurrected the two-party system; Stephen Douglas, who ensured the Democratic Party survived the Civil War; William Jennings Bryan, who transformed the Democratic Party from a conservative to a progressive party in a single election; Al Smith, whose campaign changed how Americans thought about Catholics and how Catholics thought about America; Thomas E. Dewey, who brought the Republican Party into accommodation with the welfare state; Adlai Stevenson, who raised the question whether someone can be too intellectual to be president; Barry Goldwater, whose campaign changed the allegiance of the Deep South to the Republican Party; George McGovern, who built a new Democratic coalition that paved the way for our first African-American president; and Ross Perot, who changed the way candidates use television and who inspired other wealthy businessmen and women to enter politics. There is also a special chapter on three recent “also rans”—Al Gore, John Kerry, and John McCain—the only three presidential nominees to have served in the Vietnam War. Their legacies cannot yet be fully assessed, but, as of this writing, they seem to be redefining the role of the presidential loser. This book also offers a series of short essays on the other men who won a presidential nomination and lost, but whose lasting impacts on our political system were, in this author’s judgment, less consequential than those featured in the chapter-length treatments.

And there is also the first chapter, which discusses the great and vital service every losing candidate has provided to the nation, which is the simple act of accepting his defeat. In many nations, losing candidates reject the electoral result and lead their nations into chaos, rioting, and even civil war. That our losing presidential candidates, often graciously, accept their defeat and make way for the winner has been essential to the success of American democracy. As William Riker noted, “The dynamics of politics is in the hands of the losers. It is they who decide when and how and whether to fight on.”

The importance of a gracious concession deserves special attention in today’s unusually polarized political environment when so many Americans seem reluctant to accept the verdict of majority rule. During the past two decades, Americans have been put on edge by the trauma of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the two wars the United States fought in response to those attacks, and the 2008 collapse of the financial markets. Politically, these tensions were exacerbated by the prior attempted impeachment of President Clinton and a series of extraordinarily close presidential elections. The closest was in 2000 when, for only the fourth time in our history, the candidate who received the largest number of popular votes did not become president. To win the most votes and still lose is an especially bitter pill; to accept this result for the good of the nation is an especially heroic act.

In each of these recent elections, and in several elections past, there were attempts by some to delegitimize the results and the presidency of the winning candidate. But every time, we have been fortunate that the losing candidate took his defeat graciously, and in so doing reinforced the legitimacy of our electoral system and of the administration elected to govern us. To do otherwise could lead to a level of rancor and chaos that could debilitate the country. It is not overstatement to say that without this essential contribution of concession from the losing candidate, the stable, resilient democracy, which is so often taken for granted in the United States, would be impossible.

CHAPTER ONE

THE CONCESSION

An election does not end when the winner declares victory; it ends only when the loser concedes defeat. This may seem a minor distinction, but it is what makes American democracy work.

Election night, November 4, 2008, Republican presidential nominee John McCain had one final opportunity to be the focus of the nation’s undivided attention before his presidential campaign concluded. And even though the election returns indicated he would be the loser, McCain wielded a power whose potency even he may not have fully appreciated.

Before Barack Obama could give his televised victory address before 125,000 ecstatic supporters in Chicago’s Grant Park, McCain first had to admit defeat. Until he did, the election wasn’t over. By tradition, McCain would get to speak first, while Obama remained out of view, his supporters still stewing with anticipation, for he was not yet the president-elect.

There was a sense of real drama when McCain finally appeared at 11:18 p.m. EST, before the television cameras and seven thousand dejected supporters who had gathered at a Phoenix, Arizona, resort. Tensions had been high during the campaign, and the nation watched to see if McCain would say anything that might lead his supporters to question the results of the day.

Obama was the first African American ever nominated for president by a major political party. As the son of a Muslim father from Kenya, his background was exotic to many. His opponents had repeatedly labeled him a radical. The world economy was in a tailspin. American troops were fighting two wars, in Iraq and Afghanistan. The two previous presidential elections had been remarkably close, and America seemed evenly divided by party loyalty and widely separated by ideology.

At campaign rallies for McCain and his polarizing running mate, then Alaska governor Sarah Palin, there had been shouts of “traitor!”, “terrorist!”, and even “kill him!” at the very mention of Obama’s name. Throughout the campaign and through Election Day, there were allegations of voter fraud and voter intimidation from both sides.

But that Election Day evening, McCain, after first hushing the boos that erupted at every mention of Obama’s name, graciously conceded his defeat and pointedly referred to Obama as “my president.” Moved by McCain’s words, the crowd stopped jeering the man now conceded to be the president-elect and instead cheered the historic nature of Obama’s election as our first African-American president.

McCain, at least for the moment, had set a tone of reconciliation that helped legitimize Obama’s election in the eyes of millions who had voted against him. This period of civility gave Obama time to reach out to those who had not supported him. Within a week of the election, nearly three-quarters of Americans professed to view Obama favorably. Certainly, Obama’s own inspirational words, which followed McCain’s that evening, had helped persuade Americans to rally to his side at that moment, but the power and importance of McCain’s address, by conveying to his supporters that it was his and their patriotic duty to be good losers, were an essential tonic to soothe the nation.

Had McCain expressed anger or bitterness at his loss, had he alleged that fraud had swayed the election, had he questioned Obama’s fitness to lead, or continued his campaign assertions that Obama’s policies would bring the nation to ruin, McCain would have widened the division caused by the passion of a presidential election. Such a response would have created political chaos and even invited violence.

Yet, McCain had done nothing extraordinary beyond performing his role exceptionally well, for our losing presidential candidates have repeatedly chosen to be good losers, and, as counter-intuitive as it may sound, they have played a crucial part in making politics in America a source of unity, not division.

We may think election-related violence is inconceivable in the United States, even in today’s highly polarized political environment. But there is always a thin line between a peaceful election and armed conflict. We acknowledge this close relationship in the way we use martial jargon to discuss our politics. Candidates battle for states, campaigns are run from war rooms, commercials are part of a media blitz, and campaign volunteers are foot soldiers. “Politics,” the Prussian military theorist Carl Von Clausewitz said, “is the womb in which war develops.”

Violent conflict is born out in other nations where the martial language of politics is not metaphorical. In the same year that McCain and Obama held their heated but ultimately peaceful contest, post-election viol

ence in Kenya left some fifteen hundred people dead and a quarter-million homeless. Also in 2008, post-election rioting killed eighteen in India, the world’s largest democracy, and five in Mongolia. Historic elections in Bangladesh led to rioting that injured one hundred. In 2010, there was post-election violence in Guinea, Belarus, Iran, and the Ivory Coast, and additional examples can be found in virtually any year to remind us, in the words of political scientist Paul Corcoran, “the transition of power is often a matter of life and death on a grand scale.” And lest we think post-election violence is confined only to supposedly immature “Third World” democracies, riots in France protesting the election of President Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007 injured seventy-eight policemen, caused more than seven hundred cases of arson, and led to the arrests of nearly six hundred people.

With the hubris that is part of being an American, we may assume our lack of protest is because, unlike other nations, our elections are fair and honest. Yet, American elections are rife with fraud, abuse, and incompetence, which are forgotten and ignored until a close election requires a recount and we realize how imprecise our balloting is.

We devote remarkably few resources to that cornerstone of American democracy: a free, fair, and accurate election process. Election standards vary widely by location, top election officials are elected partisans, and poll workers receive minimal training and compensation. There are multiple examples in every election cycle of outright corruption and concerted efforts to disenfranchise one set of voters or another (particularly minority voters), but violations of election law are seldom prosecuted, and the penalties are minimal for those that are. The result of virtually any close election could be in dispute because running efficient, professional elections is not a national priority. We have minimal interest in probing the question of the fairness of our elections. Few states even have a mechanism for challenging an election result.

Nor is the tradition of relatively peaceful elections in the United States due to any special American aversion to violence. Rioting is a time-honored tradition in America. We have had riots associated with race and religion. We have had riots related to political disputes, dating back to the Whiskey Rebellion. We have had riots against war and the military draft. We have had riots against police brutality, and riots that involved police brutality, such as occurred during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. We have had labor riots, prison riots, riots by anarchists, and even riots after sporting events—an average of ten to fifteen per year, in fact—and by fans of both losing and winning teams. And yet, while we riot after football games, we do not have violence related to our greatest electoral prize, the presidency.

The notable exception, the election of 1860, proves the rule. The refusal of the South to accept Lincoln’s election led to our Civil War and six hundred thousand war dead. But the behavior of the losing candidates in that election in no way contributed to the dissolution of the Union, as we will see in the subsequent chapter on Stephen Douglas. Further, that catastrophe has perhaps been a lesson for subsequent generations of the dangers in rejecting the democratic process and the rule of law. In his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln said men had fought and died in the war so that the “nation might live.” In less dramatic fashion, each presidential election tests Lincoln’s concern that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The losing candidate, then, must set the tone of acceptance, or at least resignation, that tamps down the possibility of violence in the wake of electoral disappointment. A group of five political scientists from five countries, including the United States, who have studied the role electoral losers play in the democratic process concluded in their 2005 book, Losers’ Consent, that “what makes democracy work . . . is not so much the success of the winners, but the restraint of the losers.”

Many losing candidates have certainly had to exercise great restraint. Four times since 1824, when the popular vote was first used to help determine the presidential winner, the man who won the largest number of popular votes did not become president because he did not receive a majority in the Electoral College. This occurred in 1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000, and there have been other elections, such as 1880 or 1960, where the margin of victory was so close as to be in dispute.

Presidential elections are almost always close, at least in terms of the popular vote. Only four times—1920, 1936, 1964, and 1972—has the winning candidate won more than 60 percent of the vote, a true landslide. In roughly half of all presidential elections, the winning candidate has received 51 percent or less of the popular vote; 40 percent of the time, because of third parties, the person elected president has not even received a majority of the popular vote.

The narrowness of these victories is masked because of our Electoral College system, which often makes the result seem more definitive than it is. In 1980, for example, Ronald Reagan received less than 51 percent of the popular vote in his victory over President Jimmy Carter and independent candidate John Anderson, but he received 90 percent of the Electoral College vote. Because of the Electoral College, we do not have a single, national election for president, but rather fifty-one separate elections conducted by the states plus the District of Columbia.

After 1860, the closest our nation has come to blows over a presidential result was in 1876, when Governor Samuel J. Tilden of New York won the popular vote by a comfortable 51 to 48 percent margin but lost the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes in the Electoral College by a single elector. To obtain that result, Republicans had engaged in outright voter fraud in three Southern states, including Florida, though Democrats had also engaged in intimidation to prevent African Americans from voting in those states.

In the uproar that followed, Democratic mobs cried, “Tilden or blood!” and fear of a renewed civil war was so real that President Ulysses S. Grant fortified Washington, D.C., with troops and gunboats to repel an expected army of Tilden supporters. But Tilden was a successful attorney who believed in the rule of law, and he declined to sanction any such offensive by those on his side. At Tilden’s urging, tempers cooled and, ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court established a method by which the election was resolved in favor of Hayes; though, in truth, behind the scenes a deal had been made—Hayes was given the presidency in return for a promise to withdraw federal troops from the South and end Reconstruction. When Tilden, an eccentric character, finally spoke publicly in June 1877, he offered comfort to his supporters, urging them to “be of good cheer. The Republic will live. The institutions of our fathers are not to expire in shame. The sovereignty of the people shall be rescued from this peril and re-established.”

In 2000, Vice President Al Gore faced a remarkably similar situation and was criticized as Tilden had been for not making a more forceful claim to the presidency. Having won the popular vote by a margin of 500,000, Gore lost the election to George W. Bush when he failed to win the state of Florida by 537 votes. Gore had said that on election night he felt considerable pressure “to be gracious about this,” which led him to concede perhaps too quickly when his own interests would have been served by waiting a while longer. Gore had called Bush to concede at about 2:30 a.m. EST the morning following Election Day, and that call was widely reported in the media. It was while Gore was en route to give his formal public concession speech that aides intercepted him and urged him to retract his concession because of tightening vote totals in Florida. Gore again called Bush who, incredulous, asked, “Let me make sure that I understand: You’re calling back to retract that concession?” Gore replied, “You don’t have to be snippy about it.”

A partial recount was halted by a 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court decision that the court itself said set no precedent. The month-long dispute had resulted in some minor scuffles—a few Gore partisans protesting in Washington, D.C., even tried to rouse a cheer of “Gore or blood” to evoke the Tilden crisis—but the tradition of a good loser is now deeply rooted in American politics.

Tensions rapidly dissipated when Gore gave a remarkably cheerful concession speech and there was no violence, even though surveys later showed that 97 percent of those who voted for Gore believed he was the “rightful” president. But once Gore had conceded, even in a private phone call, the perception was that he had lost and then was trying to overturn the results; had he never conceded, the public perception might have been that both candidates had an equal claim to the election.

Gore is not the only cautionary tale of a loser willing to concede too soon. President Jimmy Carter conceded to Ronald Reagan on Election Day in 1980 with a telephone call at 9:01 p.m. Eastern time, followed by a speech an hour later at the Sheraton Washington Hotel ballroom. Carter had been urged to delay his concession until 11 p.m. Eastern time, after the polls were closed on the West Coast. But Carter was worried the public, knowing that Reagan was projected to win by a wide margin, would think he was sulking in the White House and he did not want to appear to be a “bad loser.”

“It’s ridiculous,” Carter said. “Let’s go and get it over with.” That decision infuriated Democrats, who thought Carter’s early concession led some voters in the West to skip casting their ballots. House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill raged that Carter had cost a half-dozen Democrats seats in Congress and perhaps two Senate seats. He yelled at a Carter aide, “You guys came in like a bunch of jerks, and I see you’re going out the same way!”

Despite what appeared to be a mistake in retrospect, Gore was not unwise in trying to avoid being labeled a sore loser, for complaints about the fairness of a result seldom receive much sympathy beyond the losing candidate’s most rabid followers. Americans simply do not want to consider that an election has been unjust or worse.

Almost President

Almost President Kennedy and Reagan

Kennedy and Reagan