- Home

- Scott Farris

Kennedy and Reagan Page 15

Kennedy and Reagan Read online

Page 15

What had never been a concern when Lincoln sacked McClellan or Truman cashiered MacArthur was now spoken about freely: the possibility of a military coup in the United States. Retired Marine Corp General P.A. Del Valle was quoted as saying that if the electorate refused to “vote the traitors out” the only alternative was “the organization of a powerful armed resistance force to defeat the aims of the usurpers and bring about a return to constitutional government.” Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman J. William Fulbright conducted his own investigation into the supposed infiltration of the senior military by ultraconservatives and concluded, in a memorandum that he published in the Congressional Record, that the political activities of senior military leaders had gotten so out of hand that there was a danger of a military coup. Fulbright noted that French military officers had revolted against the De Gaulle government over Algerian independence just two years before.

For his part, Kennedy agreed that in the political atmosphere of the early 1960s a coup was possible, but insisted “it won’t happen on my watch.” Kennedy did, however, demand that senior military officers, particularly those with strong ties to the far right, such as Admiral Arleigh Burke and General Edwin Walker, who later became a leader within the John Birch Society, clear all planned public remarks with the White House before delivering them, which critics complained was an attempt to “muzzle the military.” Kennedy directed aides to monitor right-wing activity and illegally used the Internal Revenue Service and other federal agencies to harass right-wing organizations and their supporters.

Kennedy also fully cooperated with director John Frankenheimer when he decided to make the 1962 novel Seven Days In May into a film, starring Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster. The book and film imagine a scenario where a military coup is attempted by anti-Communist extremists. Kennedy offered to let Frankenheimer film at the White House, and he conveyed to Frankenheimer that making the film was “a service to the public” because it would alert Americans to the dangerous political activities of some senior commanders.

Neither Kennedy’s fractious relationship with elements of the senior military nor Reagan’s effusive embrace of all things military can fully explain the partisan divide that emerged within the military, beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, but such a divide was created and still exists. Where once military officers such as General George C. Marshall argued it was improper for professional soldiers to even vote, a study conducted in 2009 found that between 1976 and 1996 the percentage of senior military officers who identified themselves as Republicans jumped from one-third to two-thirds, while those professing to be political moderates dropped from 46 percent to 22 percent. Other studies have suggested the key moment when the conservative leanings of the military became more pronounced was when an all-volunteer army was instituted in the 1970s and a disproportionate number of recruits came from the conservative South. Of course, the increasing popularity of the Republicans in the South is also a legacy of the Kennedy era.

To whatever degree Kennedy’s wartime experiences gave him trouble with the military as president, the most important event of the war for him was neither his day-to-day duties nor his heroism, but the death of his elder brother, Joe Junior. Joe Junior was in naval aviation in the European theater where he had flown the requisite thirty missions that should have sent him stateside in the spring of 1944, but Joe volunteered for additional duty. He had certainly read of his younger brother’s heroics in the Pacific, and while he congratulated Jack on his “intestinal fortitude,” he also seemed to rebuke his brother by asking in a letter, “Where the hell were you when the destroyer hove into sight?”

Whether Joe Junior was motivated in part by envy of his younger brother, worried that his war record had still left him short of some ideal he had in his mind (or believed was in his father’s mind), or he was simply motivated by patriotism, Joe volunteered for a particularly dangerous mission whose odds of success were close to nil. To eliminate the heavily fortified Nazi bases used to launch the terrifying unmanned V-1 flying bombs aimed at England, a plan was developed by which PB4Y aircraft (a version of the Liberator bomber) would be emptied and filled with twenty-two thousand pounds of explosives. The pilot would fly the plane partway across the English Channel to a designated point, where he would then parachute out while another plane remotely guided the suicide plane to its target.

On August 12, 1944, Joe took off with his copilot. They had been in the air only a few minutes when the plane exploded. It was said to be the largest human-caused explosion to that point in history, and its power would only be surpassed by the atomic bomb. The blast damaged buildings in a small English town miles away. “Not a single part of Joe Kennedy’s body was ever found,” reported Doris Kearns Goodwin.

Jack Kennedy found himself “completely powerless to comfort his inconsolable father,” who locked himself in his room for days to grieve. Joe’s dream of siring America’s first Catholic president seemed to have ended. Jack had once boasted to Inga Arvad that he might become president one day, but his family had been “sure he’d be a teacher or a writer.” His brother’s death left Jack lost and confused. He had spent his entire life measuring himself against Joe. Now that yardstick was gone. As the war wound down, Jack had no idea of what he should do or even what he wanted to do. He would need time to sort things out and map out his future. So would Reagan.

CHAPTER 9

ANTI-COMMUNISTS

Communists were infiltrating American labor unions. It was that suspicion, shared by John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan in the years after World War II, that hardened into a severe antipathy toward Communism that both men would carry over into their presidencies. Kennedy twice risked nuclear war to confront the expansion of Soviet influence, first in Berlin and then in Cuba, while President Reagan called the Soviet Union an “evil empire” and pursued a set of policies he believed would bring the Soviet Union—and Communism—to its knees.

As the son of one of the richest men in the world and as a Roman Catholic, Kennedy’s anti-Communism was ingrained. It was also an exceedingly popular position among his Irish Catholic constituents in Boston and explains why Kennedy, while a freshman congressman in 1947, became famous for domestic Red-hunting well before his fellow freshman Congressman Richard Nixon and a freshman senator named Joseph McCarthy. It is not surprising, then, that Kennedy later dismayed liberals by being the only Democratic senator who refused to vote for McCarthy’s censure.

Reagan’s anti-Communism, which led him to become an informant for the FBI, was not ingrained but was the result of a lengthy ideological journey. It began, friends claim, in the late 1930s when Reagan sought to join the Communist Party. It ended a decade later with Reagan so fearful domestic Communists intended to maim or kill him that he began to carry a gun.

Given Reagan’s later views of Communism, the idea that he flirted with becoming a Communist himself seems unbelievable, but friends insist it is true. Because Roosevelt’s New Deal programs had helped save the Reagan family from impoverishment, and given his father’s previous work on behalf of the Democratic Party, Reagan, too, became a proud liberal Democrat.

As the women he dated discovered, Reagan loved nothing more than to expound at length on his political beliefs, and he remained troubled by the continued suffering of so many as the Great Depression extended through the 1930s. The Depression caused loyal Americans from coast to coast to question whether capitalism was, in truth, the best economic system available. California had a close brush with socialism with writer Upton Sinclair’s 1934 EPIC (End Poverty in California) gubernatorial campaign, which the film studios played a major role in defeating. There was also a small cadre of Communists or Communist wannabes in Hollywood, particularly among screenwriters, who tended to be more radical than their acting brethren. Reagan, who fancied himself a writer at heart, knew some of these radicals and discussed and debated politics with them.

Author and screenwriter Howard Fast s

aid that Reagan once inquired about becoming a member of the Communist Party. Fast, who was a member of the party for fifteen years, claimed Reagan was adamant that he wanted to join, but party leaders doubted the depth of Reagan’s convictions. In Fast’s words, party leaders considered Reagan “a flake . . . [who] couldn’t be trusted with any political opinion for more than twenty minutes.” Reagan friend Eddie Albert confirmed that “there were conversations” about Reagan becoming a Communist, but that friends talked him out of it—saving his future political career.

After the war, Reagan had no plans for a political career. Still just thirty-four years old, he had assumed that once he was out of uniform he would resume his very promising acting career. He especially hoped he could finally convince Warner Brothers to begin starring him in Technicolor Westerns. Instead, Reagan found he was not much in demand. Even though he was being paid more than $150,000 per year under his Warner Brothers contract, the studio advised Reagan to relax until they could find the right acting vehicle for him.

But Hollywood had changed during the war. The main fare was no longer escapism from the troubles of the Depression, but realism that reflected the cynicism and anxiety of the postwar world. The light, sunny comedies that had been Reagan’s specialty gave way to film noir, in which the leading man is a morally ambiguous hero often led to his doom by a femme fatale. As a movie cowboy, Reagan had probably imagined wearing the proverbial white hat, but even adult Westerns began to have a noir-ish feel. Reagan was simply incapable of projecting the moral ambiguity the genre required, and he was too nice to seem menacing in the role of villain. In a career that included more than fifty feature films and dozens of television roles, Reagan played a villain only once, in his final film, The Killers (1964), and he regretted doing it even once.

When Warner Brothers put Reagan in the type of films that sought to capture his prewar appeal, they usually flopped. One such film, That Hagen Girl, resulted in one of the truly unfortunate romantic pairings in cinematic history. Nineteen-year-old Shirley Temple played the fortyish Reagan’s love interest.*

* Reagan was thirty-six years old when he made That Hagen Girl, but he was still recovering from a near-fatal bout of viral pneumonia that made him look years older during filming.

Reagan’s stalled career was even harder for him to bear because his wife, Jane Wyman, was becoming as one of Hollywood’s most acclaimed actresses. Reagan, as his own mother noted, primarily played “just himself” in his movies with little attention to developing a character. Reagan was a craftsman actor, as opposed to an artistic actor, and was amazed at how Wyman prepared for her roles, sometimes staying in character even at home, so concentrated on her work that she would “come through the door, thinking about her part, and not even notice I was in the room.” Wyman starred in a string of celebrated films from 1945 to 1948 that included Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend; The Yearling, for which she was nominated for an Academy Award; and Johnny Belinda, for which she won the Academy Award for best actress for her portrayal of a deaf mute.

The imbalance in their careers put pressure on the couple’s marriage; Hollywood would have been one of the few places on earth in those days where a wife might earn more money and fame than her husband. But there were other stresses as well. While Wyman was filming The Yearling, Reagan contracted viral pneumonia, which nearly killed him. While he was still hospitalized and fighting for his life, Wyman gave birth to a baby girl four months prematurely. The Reagans named their daughter Christine, but she died the day after her birth in June 1947.* To occupy his time, and partly at Wyman’s suggestion to get him out of the house, Reagan became more active in the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). When he first came to Hollywood, Reagan had been reluctant to join SAG, but after a “pep talk” from a fellow actor, Reagan soon became a “rabid union man.” He later enjoyed boasting that he was the only president ever to have held a union card—though SAG was an unusual union. Its members included some of the highest paid people in America, and Reagan credited the work of some of the industry’s biggest stars—James Cagney, Cary Grant, and Charles Boyer, among others—with ensuring SAG’s success.

* By coincidence, Kennedy and his wife would also know the sorrow of losing a newborn—twice. In 1956, Jackie Kennedy gave birth to a stillborn daughter they named Arabella, and in 1963, while Kennedy was president, a little boy they named Patrick died following an emergency caesarian section in August 1963.

Historian Garry Wills has suggested that the SAG union set well with Reagan because it fit his notion that the strong were obliged to help the weak, rather than in a typical union where the goal is to make the weak strong. Also, since film or television stars—whether they were SAG members or not—could still negotiate their own salaries, the union did not restrict how individual merit could be rewarded. The union did not try to level economic benefits among its members. Given the size of Reagan’s contract, he would certainly have been loathe to do so.

Baby Christine’s death seemed to doom an already troubled marriage. Still, Reagan was astonished to read Wyman quoted in the newspapers as saying that their marriage was over. When it was revealed that Wyman was having an affair with her Johnny Belinda costar Lew Ayres, Reagan told gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, “If this comes to a divorce, I think I’ll name Johnny Belinda as a correspondent.”

Publicly, Wyman said the cause of her divorce was that she and Reagan no longer had anything in common. Privately, she said she found Reagan’s increased involvement in politics intolerably boring—“I’m so bored with him, I’ll either kill him or kill myself,” she said—particularly since Reagan professed no interest in hearing her opinions. Others who knew and dated him also testified that Reagan’s idea of a conversation was to give a lecture. While Reagan always saw himself as a victim who did not want a divorce, he tacitly acknowledged the truth of some of Wyman’s complaints late in life when he was asked, given how often he discussed politics at their kitchen table, whether Wyman was a Republican or a Democrat? “I don’t think I ever heard her say,” Reagan said.

Like Reagan, Kennedy had been enthralled with politics before the war, but had no real sense that it would be his career. The death of his brother Joe had left him confused and adrift. He had always measured himself against Joe; now that yardstick was gone. Kennedy had daydreamed about running for office before, but his brother had claim to a political career, so Kennedy had contemplated the law, academics, or journalism as alternative professions—professions his own family thought suited him better than politics.

In an interview in 1957, Kennedy’s father created the legend that after his eldest son’s death he had simply and deliberately told Jack, “Joe was dead and that it was therefore his responsibility to run for Congress.” In truth, the process by which Joe and Jack mutually agreed that Jack should pick up Joe Junior’s mantle was a much more complicated process.

Those who knew the Kennedys said the impact of Joe Junior’s death upon his father “was one of the most severe shocks . . . that I’ve ever seen registered on a human being”—this at a time when many families had received the worst possible news from overseas. Joe Junior meant more to his father than being just the favored eldest son. As Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote, “It was as if Joe Junior’s life belonged to Joe Senior as a second life for himself, a second chance to bring the name of the Kennedy family to the heights of national greatness. With Joe Junior’s death, all these plans seemed forever destroyed.”

Jack was initially at a loss as to how to comfort his inconsolable father. He was dealing with his own feelings of grief and loss and said he felt “terribly exposed and vulnerable” in the months after Joe’s death. He also felt some “unnamed responsibility” had fallen upon his shoulders as he now moved into the position of eldest Kennedy sibling. When Joe was alive, Jack knew that the responsibility for fulfilling his father’s dreams rested on his brother, which had left him free to do whatever and be whomever he liked. Now, though h

e and his father had not had the direct conversation Joe Senior would later invent, he knew his life had changed and he would have little freedom to choose his own future.

It also took Joe Senior time to adjust to the idea that he would need to transfer his filial ambitions to Jack. Somehow unaware of Jack’s reputation for being the life of every party, Joe said his impression of Jack was that he was “rather shy, withdrawn, and quiet. His mother and I couldn’t picture him as a politician.”

Before his parents pictured him as anything, Jack needed to further recuperate from the various health problems that he had exacerbated through his war service. After being released from Chelsea Naval Hospital in January 1945, Jack went to Phoenix to recover in warm weather. Each night at precisely 5:00 p.m., his father called him and they had lengthy discussions about world news and national events. It was the most time Jack had ever spent talking to his father, expressing his own ideas, and Joe began to notice qualities in his second son that he had overlooked before. Surprised by how impressed her husband was with Jack’s intellect, Rose Kennedy thought these conversations were “the one thing that seemed to brighten [Joe] up.”

Before father and son determined that Jack would definitely go into politics, Kennedy tried his hand at journalism. Joe pulled some strings and convinced the Hearst papers to hire Jack as a special correspondent to cover the first United Nations conference that convened in San Francisco in April 1945. Kennedy earned $250 per article and eventually filed seventeen three hundred–word stories for Hearst during the conference.

Generally his dispatches warned against unrealistic expectations of good relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, saying that twenty-five years of mutual mistrust “cannot be overcome completely for a good many years.” He added that it was a pity “that unity for war against a common aggressor is far easier to obtain than unity for peace.” One of his articles argued the United States could not afford a postwar arms race with the Soviets without destroying the U.S. economy and even democracy. Editors who thought Kennedy was providing simplistic analysis to a complicated subject spiked it.

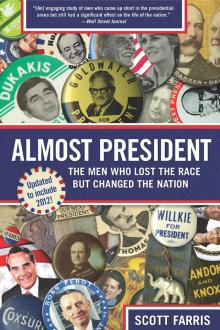

Almost President

Almost President Kennedy and Reagan

Kennedy and Reagan